|

|

|

By around 100,000 years ago at Kalambo Falls in Zambia, Homo erectus was making very well made bifacially flaked hand axes. The use of soft hammer tools, made of either antler, ivory or wood, had long been in use by that time. Desmond Clark, who excavated Kalambo Falls, remarked that "it’s amazing that a different species was able to make such skillfully crafted stone tools." The Kalambo Falls site produced some of the worlds first well-made "thick" bifaces. About 80,000 years later, modern humans began to make the worlds first very thin bifaces during the Solutrean in southern France. During the next 20,000 years the art and skill of flintknapping, and the invention of many more lithic technologies, rapidly developed throughout the world. |

|

|

All of our ancestors have used flaked stone tools sometime during the last 4 or 5 thousand years. Flintknapped artifacts have been involved in every part of the human drama. Without them, the Industrial Revolution may never have happened. The majority of all stone tools were manufactured for domestic uses, for hunting, processing food, making clothes, jewelry, etc. Some spear and arrow points were made for weapons of war and defense. The most elaborate and impressively flaked stone artifacts were made for ritual purposes. They are the artifacts that many of today’s flintknappers are trying to duplicate. These objects were made by craftsmen who had developed the highest degree of the flintknappers skill. Most of them were made for offerings to the dead and buried in graves or tombs. Others were made for offerings to various gods and thrown into sacred wells or placed under alters, stelas and in pyramids. Still other ritual tools, like dance swords, sucking tubes, pipes or sacrificial knives, may have been used by high-ranking religious figures or shamans on special events or on specific calendar days. Ritual tools were used for everything from blood sacrifices to healing ceremonies. |

|

|

|

|

There was a need for flintknapped tools long after the Industrial Revolution and the age of metal. In fact, in Europe, a very intensive, commercially driven, flintknapping industry developed around Brandon, England’s gunflint trade. For example, during a six-year period in the late 1800’s just one of many companies, the R. J. Snare Company, produced more than 20 million gunflints. In 1953 a Mr. Avery "once succeeded in knapping 400 gunflints in an hour!" An example of recent domestic use of stone tools occurred on the Island of Cyprus. Until the 1950’s, farmers were using threshing sledges that were fitted with hundreds of flint flakes. These sledges were pulled by animals over sheaves of grain to break them down before the final winnowing process. Another recent example of a commercially driven use of stone tools was made by a company called Aztecnics. They were manufacturing and selling surgical scalpels mounted with different sizes and shapes of obsidian blades. Good quality obsidian can produce a cutting edge 500 times sharper than the sharpest steel scalpel blade. |

|

|

|

|

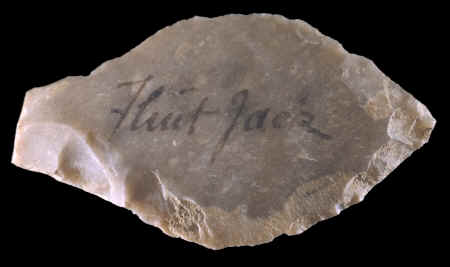

Scientists and "educated Europeans" first began to study and duplicate ancient lithic technologies in the 1800’s. What little understanding there was of controlled fracturing of stone, at that time, was almost exclusive to the stone masons and gunflint makers. Around 1850, one of the earliest knappers to duplicate prehistoric artifacts was an Englishman named Edward Simpson, also known as "Flint Jack." He was one of the earliest experimental stone tool makers who became proficient at replicating several different types of ancient stone artifacts. From the mid-1800’s to about 1960, only sporadic studies and published reports appeared on the subject of flintknapping. In 1919, W. H. Holmes, a Smithsonian archaeologist, published illustrated techniques on flintknapping. But, he wasn’t reporting from his own flintknapping experiments but from descriptions taken from other people who had observed native cultures or from "old men who had knowledge of the work in days preceding the coming of the gun." It wasn’t until the 1960’s with people like Don Crabtree and Francois Bordes that the study of lithic technology by experimental archaeology began to really take off as a much more intensive scientific study. |

|

| CONTINUE ON TO PAGE THREE | |

|

"REFERENCES" 2005, Bostrom, Peter A., "A Short History of Flintknapping," Modern Lithic Artists Journal, Vol. 1 January, pp. 3-6. 1898,

Snyder, J. F., "The American Archaeologist, Vol. 2 Part II,"

"Counterfeiting Indian Relics," pp. 131-133. |

|