|

||

|

||

|

"To be published is to be seen." This basic concept is fundamental throughout the entire art world."------2005, Tom Onken.

By Pete Bostrom

Flintknapping is the term we use for the many different flake removal

technologies that were used to produce the "majority" of all stone

tools made on the planet. This process is accomplished by a multitude of

various techniques and tools. But the basic theme involves reducing the

volume of a stone by removing flakes. This is achieved by either direct,

indirect or pressure flaking until the desired shape is obtained.

Flintknapping can be traced farther back in time than any other technology. |

||

|

||

|

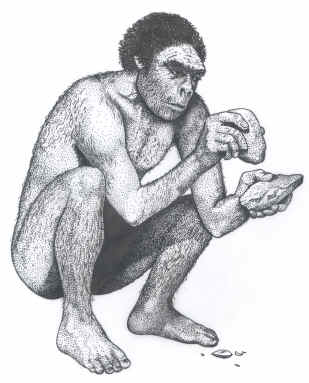

Flintknapping crosses evolutionary boundaries. In fact, the farther back in time that archaeologists look, stone tools seem to keep reappearing. The archaeological record has shown that several different species of humans were producing stone tools. The earliest stone tool manufacturing sites are between 2 and 3 million years old. The most recent discovery is Homo floresiensis or the so-called "Flores Man" also known as the "hobbit." This small 3-foot tall hominid was making simple flake tools on Flores Island, Indonesia for approximately 95,000 years and as recently as 13 thousand years ago. Other human species besides Homo sapiens were also prolific tool makers. Homo habilis, Homo erectus and the Neanderthals are three more examples. They were making stone tools far longer than modern humans were and, comparatively speaking, Homo sapiens has been flintknapping for only a few seconds of the human time-line. |

||

|

||

|

If you consider all the different forms of flintknapping that have ever been done it would seem that stone has been flaked into every conceivable shape. The archaeological record shows a slow, progressive development of lithic technology. The first stone tools began to be made sometime during the Lower Paleolithic period in Africa. Flintknapping has evolved from the simple flake tools of the Oldowan stone tool industry to very complicated eccentrics made during the "golden age" of the Mayan culture. Up until a few hundred thousand years ago, stone tools were very crudely made, consisting mostly of simple flakes, choppers, cleavers and hand axes. The majority of them were manufactured with simple stone hammers. |

||

| CONTINUE ON TO PAGE TWO | ||

|

"REFERENCES" 2005, Bostrom, Peter A., "A Short History of Flintknapping," Modern Lithic Artists Journal, Vol. 1 January, pp. 3-6. 1898,

Snyder, J. F., "The American Archaeologist, Vol. 2 Part II,"

"Counterfeiting Indian Relics," pp. 131-133. |

||