|

|

|

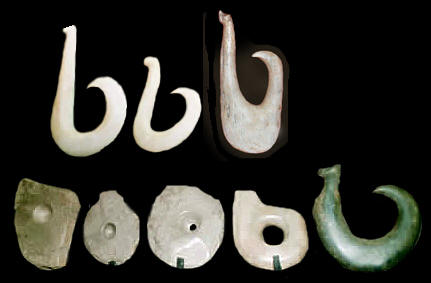

Composite v-shaped hooks are the most complex of all the fishhooks. They are two piece hooks that have a shank with a sharpened spike set into it at approximately a 45 degree angle. In North America, these types of hooks have been found on sites in Florida and Alaska. |

|

|

|

|

Halibut hooks are even more complex. These large composite fishhooks are both u and v-shaped. They were developed by Northwest coast Indians to catch large bottom-feeding halibut. The line was attached to the center of the shank instead of the end, like most fishhooks. |

|

|

|

|

Fishermen made their fishhooks from almost every type of raw material. Sometimes from necessity and not by choice. One extreme example is found on Easter Island where human bone, stone and wood was used to make fishhooks. They didn't have much of a variety of raw materials to choose from. If they did they may have replace their stone fishhooks in favor of something else. Bone was probably the most commonly used material. Turkey and deer bone are two of the most commonly used materials. The toe bones of deer were used to make small hooks and larger hooks were made from the long bones. The baculum bone from raccoon is also reported from composite fishhooks found in Florida. |

|

|

The most exotic bone that was used to make fishhooks is human bone. Easter Island and other Pacific islands have reported finds of fishhooks made of human bone. Heyerdahl describes pieces of worked human bone from a cave site, "Twenty-three pieces of human bone display evidence of cutting and/or polishing on one or more surfaces. Twelve may be blanks for manufacturing fishhooks." From a ceremonial cremation site he also reports, "There are 41 fragments of bone fishhooks---. Materials are mammalian long bones, probably human---." Also from a house site he reports, "Nine pieces of human bone, exhibiting cutting along one or both ends and sides, were found. These undoubtedly represent pieces discarded in the process of the manufacture of bone fishhooks." |

|

|

Stone is probably the rarest material that was used to make fishhooks. No archaeological site in North America has ever produced a stone fishhook manufacturing industry. There have been finds of hooked pieces that may look like a fishhook but they are singular discoveries that never have any accompanying manufacturing debris. But there are very large numbers of modern-made fishhooks. Heyerdahl even refers to these North American examples in one of his books by mistake but mentions early examples of "clever counterfeits" from Easter Island. The early Easter Islander's did make very finely crafted stone fishhooks. Heyerdahl writes that, "Due to their unique form and exquisite workmanship, the beautiful Easter Island stone fishhooks have been frequently mentioned and illustrated as outstanding samples of primitive art." |

|

|

Fishhooks have also been made from wood, shell, ivory, cactus spines, palm spines, copper and bronze. Most ancient fishhooks were made from organic materials that decay unless they are found in such places as frozen ground, dry caves or Florida rivers. So it's difficult to know how many were being used by ancient cultures. On-the-other-hand, metal and stone fishhooks have survived. Bronze Age fishhooks in Europe were being made at least 3,000 years ago. Copper fishhooks from the Old Copper Culture in the Great Lakes area of North America, date to at least 6,000 years ago. |

|

|

|

|

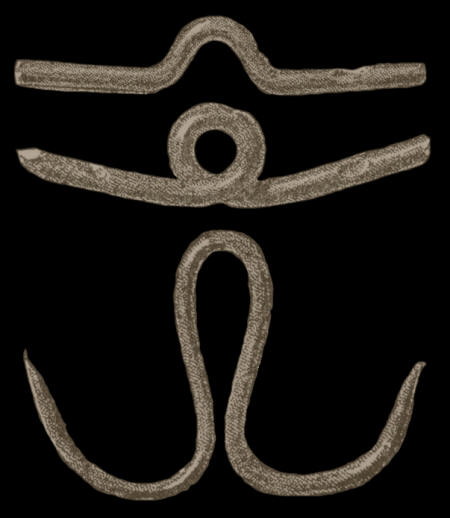

Archaeologists have speculated about how some similarly designed fishhooks were developed within different cultures that were separated by great distances. For instance, the single piece circular or curved shell fishhook is found archaeologically in Oceania, Ecuador, southern Peru, northern Chile and in southern California around Santa Barbara. Landberg suggests that fish were the trans-Pacific carriers of this particular design of fishhook. This theory originates from tag release and recovery data that show that three species of tuna are capable of long range migrations. Fishermen located many thousands of miles apart may have been retrieving foreign fishhooks from the stomachs of freshly caught fish. |

|

|

|

|

Authors could write volumes of books about fishhooks. They have such a great depth of time in the archaeological record. It would be fascinating to see a map of the world with the designs and the precise dates of the first use of a fishhook in each area. To know how many times such a simple tool was separately invented would provide an extraordinary insight into the process of human development. |

|

|

"REFERENCES"

1883,

Phillips, Barnet, "The Primitive Fishhook," The Century Illustrated

Monthly Magazine, Vol. XXV, No. 6, pp. 901. |

|